For an environmental and expressive awareness of parametric architecture.

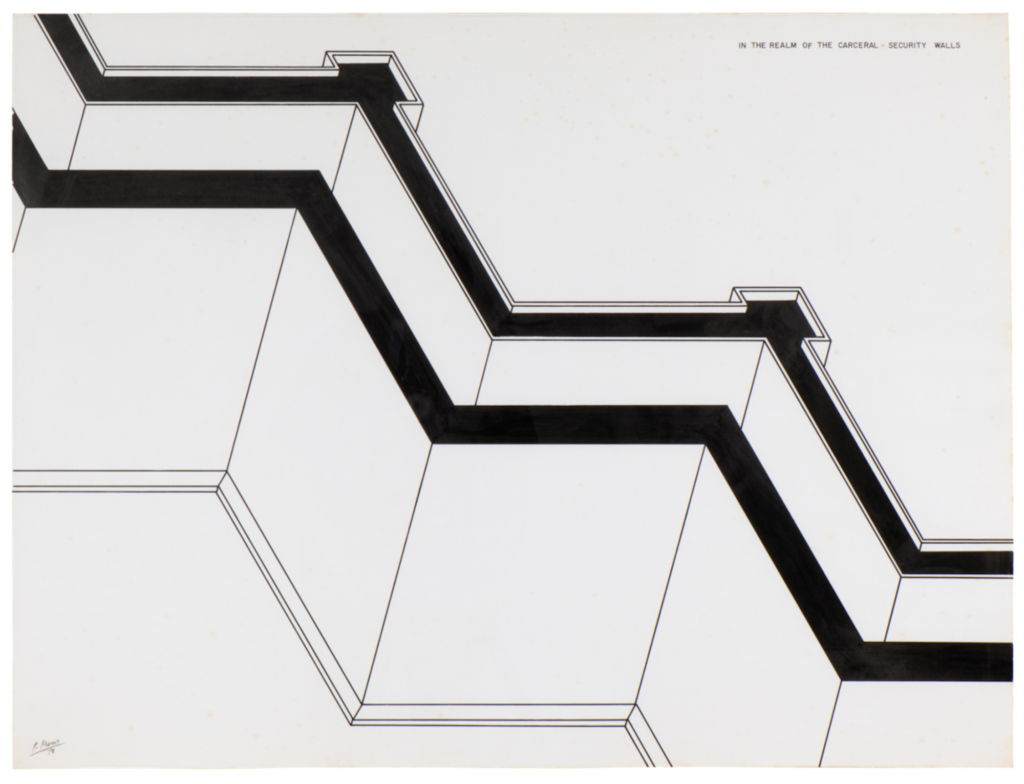

In the early 1970s, the American artist Robert Morris developed a deep interest in the ideas of Michel Foucault. One of his most significant expressions is the series of drawings and engravings In the Realm of the Carceral (1978), inspired by reading the French philosopher’s seminal essay, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975).

As Foucault argues, the original idea of modern prisons is not so much inspired by the Enlightenment’s idea of ‘resurrection through education’, but rather a milder continuation of the older, more violent punishments of the offender, from torture to killing, translated into harsh and endless imprisonment. Incidentally, during the tough self-imprisonment for the Covid19 pandemic in Italy, I found one of those etchings/acquetints online, bought it and hung it on a wall in my studio.

The large size of the print signed by Bob Morris makes it look like a kind of architecture, itself suspended above my head, to ponder on the construction of the universality of art. In this minimal/conceptual representation of the prison, the artist actually shows the anxiety of the condition of imprisonment through straight black lines on a white background, more or less marked but all tending to define that anxiogenic field – psychological and ‘technical’ at the same time – where anyone might have to spend his or her life imprisoned, either due to legal constraints or existential destiny.

All true artists aspire to produce works of this kind, which can ‘speak’ to any person, regardless of the political condition they are experiencing: and by political (from the ancient Greek, πόλις) I mean precisely how people can live as freely as possible in the context of urban territories, how they can cope with the harshness and pleasures of confinement in limited places, alien to the natural environment, increasingly controlled by governments and at the same time risky, whatever the city: Los Angeles or Rome, Detroit or Milan, Paris or Singapore.

READ ALSO – Thom Mayne: the bad boy of architecture

There is no doubt that in the political context – as I understand it here – the greatest responsibility in trying to make the city a better place to live in and as much in harmony with the surrounding nature as possible lies in the work of the architect, a contemporary author who accepts to deal not only with the functions, necessities, bureaucracy and financial problems of construction, but also with the more difficult aesthetic problems of context and environment that other arts rarely have to face.

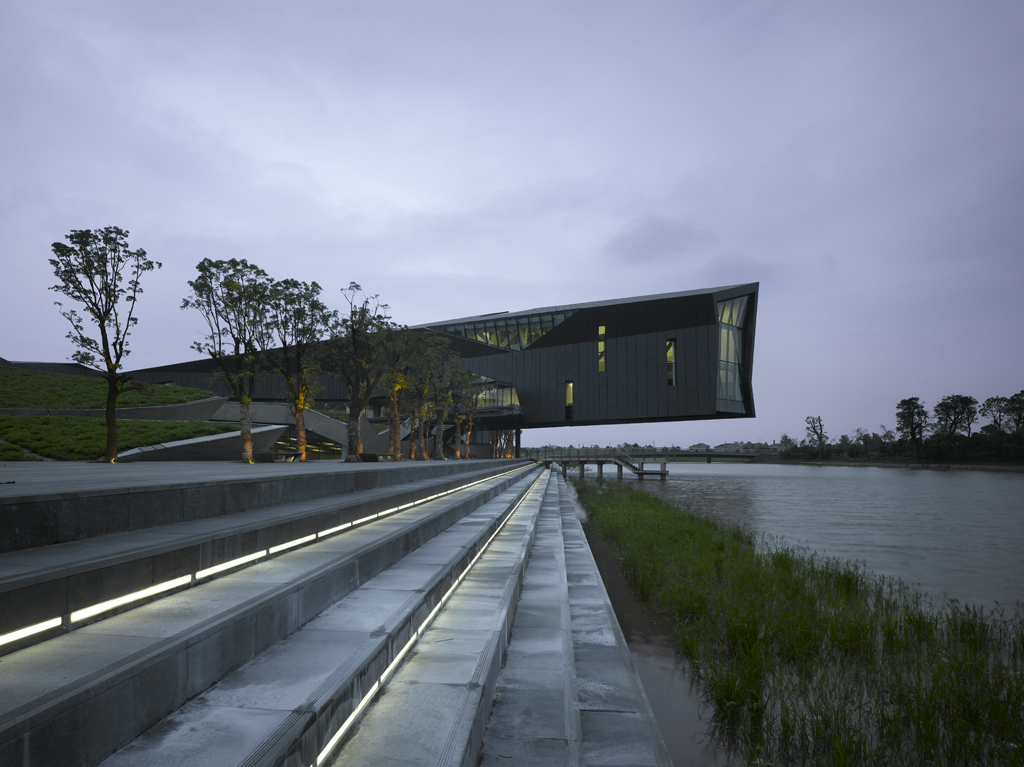

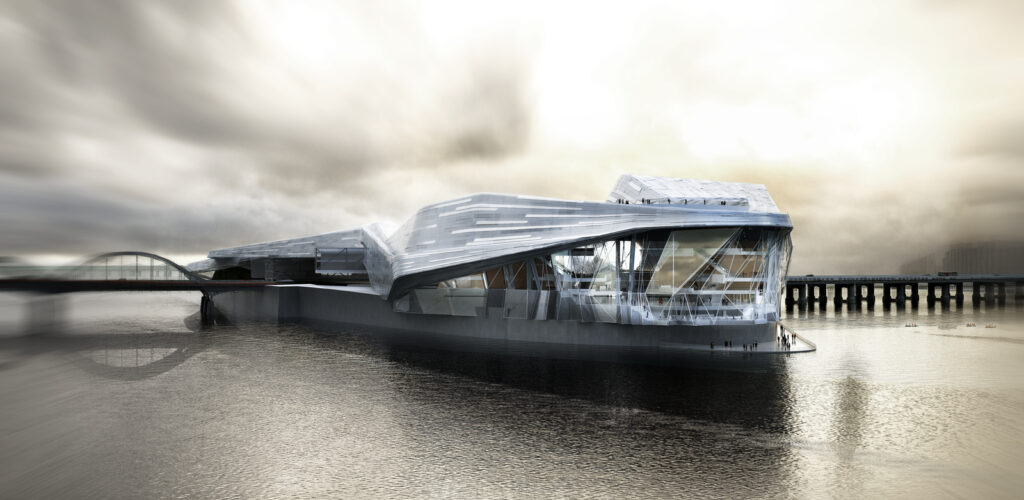

The answer, the many answers that in sixty years of work Thom Mayne has given to the rules of this contract of the architect’s social responsibility are not only based on his and his teams’ intellectual skills in technically shaping the forms of buildings – from the inside to the outside: but have a lot to do with a vision of the urban landscape as an artificial/natural environment, considered as a global garden of sculptures, and on his constant pursuit of freedom for how architecture can be created and experienced: and perhaps even extinguished, as its usefulness runs out.

The strongest and most characteristic sign of this quest for freedom that can be read in Mayne’s work is the attempt to design and not to be designed by some formalistic vocabulary, but with the intention of experimenting in each project a different set of rules for composition: where fields, fragments, holes, curves, blurs shape the space of living, from residential to educational, from monumental to small scale, in a grand experiment of “planned freedom”. In this, the standing of his buildings in the earth’s environment – from democratic California to capital/communist China – is for Thom a ‘second nature’, albeit one made of artificial forms, materials and construction techniques, the only ones that allow the designer to maintain his own identity. That is, if one does not want to give up the role of designer-inventor, to turn into a vertical gardener (or horticulturist) and delegate the sustainability of the building to the planting and cultivation of greenery (trees, lawns, flowers) inside – or more conveniently on top of – buildings, as certain architects do to distinguish themselves for the purposes of that marketing that must inevitably pay a price for greenwashing in the real estate business. Whether they are what a true pioneer of sustainable architecture such as Emilio Ambasz calls his “children, grandchildren and not a few mongrels” or genuine experimenters in sustainable building solutions, they all risk being lumped together under the convenient, obsolete and ultimately meaningless label of “Green Architecture” if their works remain isolated from the social and environmental context.

Immune from marketing contaminations, Thom Mayne has instead long acted at the heart of the environmental problem, urban development and the ‘political’ control over its limits. So as early as the beginning of the 2000s, with UCLA, Sci-Arc and the Art Center (with then director Richard Koshalek) he spearheaded the great L.A. project. Now: a meticulous exploration of the reality of the Angeleno area on all levels, pragmatically far from the narrative synthesis of Rayner Banham and the ideologism of Mike Davis, respectively authors of Los Angeles, The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971) and City of Quartz. Excavating the future of Los Angeles (1990), memorable texts on Los Angeles and its area that have contributed to creating its myth as a paradoxical and impossible city, through different tones. A magnum opus consisting of 4 volumes (2001/2006), L.A. Now is still a useful handbook for anyone who wants to organically tackle the redesign of even small parts of the City of Angels. Thus the research conducted by the team led by Mayne for this large census has a natural outlet in a fifth volume, Combinatory Urbanism. The Complex Behavior of Collective Form (2011) that presents theory and practice followed in the development of not entirely utopian projects, such as the one for the Los Angeles State Historic Park. Focusing on a decisive urban planning operation involving the relocation of Dodger Stadium and restoring green spaces and residences to the area, the design of the large park overlooking Downtown included the revitalisation of the Los Angeles River, unknown to most and channelled between two concrete walls since the late 1930s.

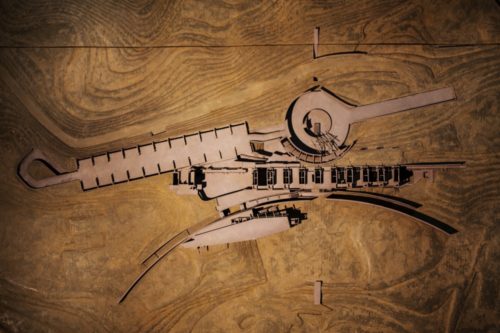

Another main theme in the discussion between nature and expression is the language ofparametric architecture, the contemporary design process based on algorithmic schemes, which allow parameters and rules to be addressedto define and organise the relationship between design requirements and the concrete construction, the final product of that process. Mayne has brought some of the most innovative experiences to this new type of design, in a series of realisations – from Cooper Union’s 41 Cooper Square (New York, 2006) to the very recent ENI complex in San Donato Milanese (2011/2023, under construction) – and before that working models (mock-ups), which constitute his second body of works of art, in some respects autonomous and ‘free’ from the constraints of the reality of the site.

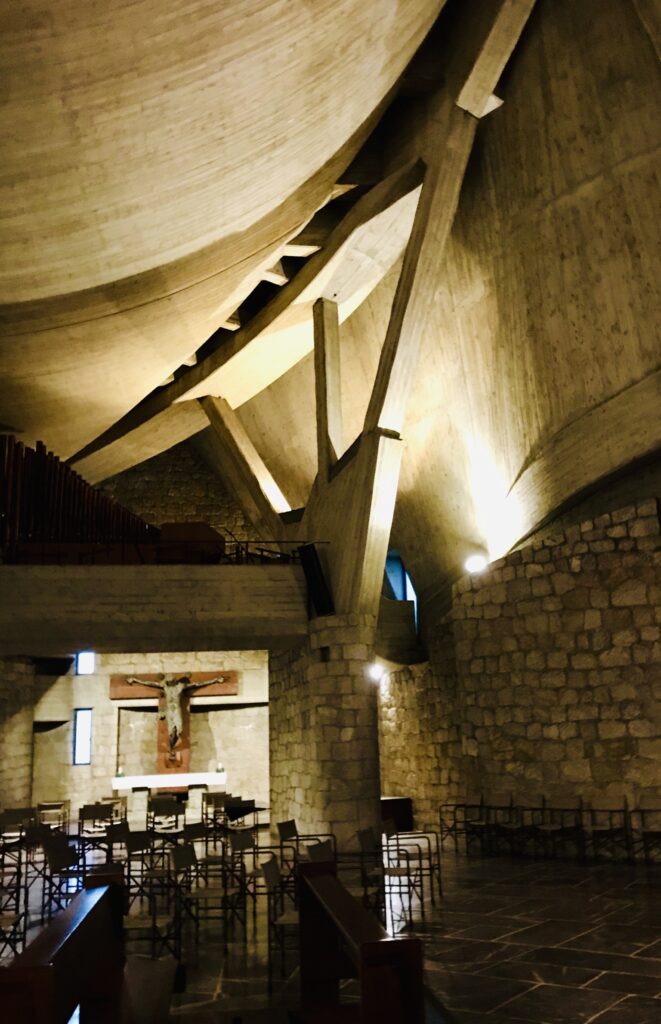

Freedom does not, however, mean denying the architect’s interest in society and its Zeitgeist, and Mayne’s architectural visions do not attempt to escape the contemporary sense of instability in life and design: they include it in the plans, elevations and sections, so that from the very first stage of the models his buildings speak of that instability, counterbalanced by the recitation of ‘impossible’ or ‘unprecedented’ forms and structures. It is no coincidence that during the journey from Milan to Perugia in December 2022 for his introductory lecture at the Seed festival in Perugia (24/30 April 2023) Thom wanted to visit the ‘Church of the Freeway of the Sun’ near Florence together, a masterpiece of the expressionist phase of the great modern master Giovanni Michelucci. Here Thom was able to reflect on the meaning of the freedom of language that Michelucci represents so well, resorting to symbols and metaphors of nature, as in the tall branching pillars that support the large hyperbolic tent like-covering of that single open space, at once a monument to honour the workers who had died, a church and a place for secular reflection on the relationship between the mystery of faith and the rawness of reality.

I have already written about the design process that brings Thom’s constructions face to face with this reality, particularly in the modelling phase in which – like the director Robert Bresson in his films – the author enigmatically speaks to the observer about the shape of things to come: and at the same time reflects on himself in art and society, searching for his personal and social location, trying to find a definition of his own being in time and space.

And again, the sometimes mysterious aspect of Thom’s models and theoretical statements is not a mask to wear over the logical mystery of statics that the resulting constructions seem to honestly and openly challenge. Rather, it resembles the armour that each person wears every day to face life and its difficulties, like the hermit crab wears the best shell it has found suitable to protect its delicate nature. Thus the model, the drawing, the rendering are no longer a costume, an accessory or an evening gown: but they become the person or the crab itself, (the building) armed with the representation of the mass and weight and materials and colours of architecture, to survive the unsustainable lightness of contemporary living, in the search for a possible new form of freedom, for the architect as well as for the community he addresses with his work.

Post Scriptum. One day in my studio, under Bob Morris’ etching, I would like to have one of Thom Mayne’s architectural models resting on the bookshelf, trying to explain to the visitor the difference between constraint and freedom in our political world, i.e. the city and its surroundings.