XTO+J-C, the most extraordinary biography ever written about Christo and Jeanne-Claude, has a beginning worthy of a novel:

It was the coldest winter in Christo Javacheff’s memory. On January 10, 1957, he and fifteen other hushed refugees stood shivering in an unheated freight car somewhere in Czechoslovakia, concealed with a shipment of medical supplies. A knifelike wind howled outside. 1Burt Chernow, Wolfgang Volz, XTO+J-C. Christo e Jeanne-Claude, una biografia, Skira / Fondazione Ambrosetti, Milan 2001 p.11

An endless story, like that of thousands of people who, to this very day, find themselves fleeing from evil in search of a better life, for themselves and their loved ones. But for Christo, who at the time was fleeing from the incomprehension and rigor mortis of a nation belonging to the post-Stalinist bloc, it was the prelude to a unique and unforgettable work or artistry, architecture, and landscape design, conceived and created entirely with his wife, Jeanne-Claude (Denat de Guillebon), who passed away several years ago.

The story of Jeanne-Claude’s life is also worthy of a novel, with a childhood as exotic as it was difficult. In fact, perhaps it was that nomadic lifestyle, among different families and places, that gave her the strength and tenacity to carry out projects that others wouldn’t have even dared to undertake.

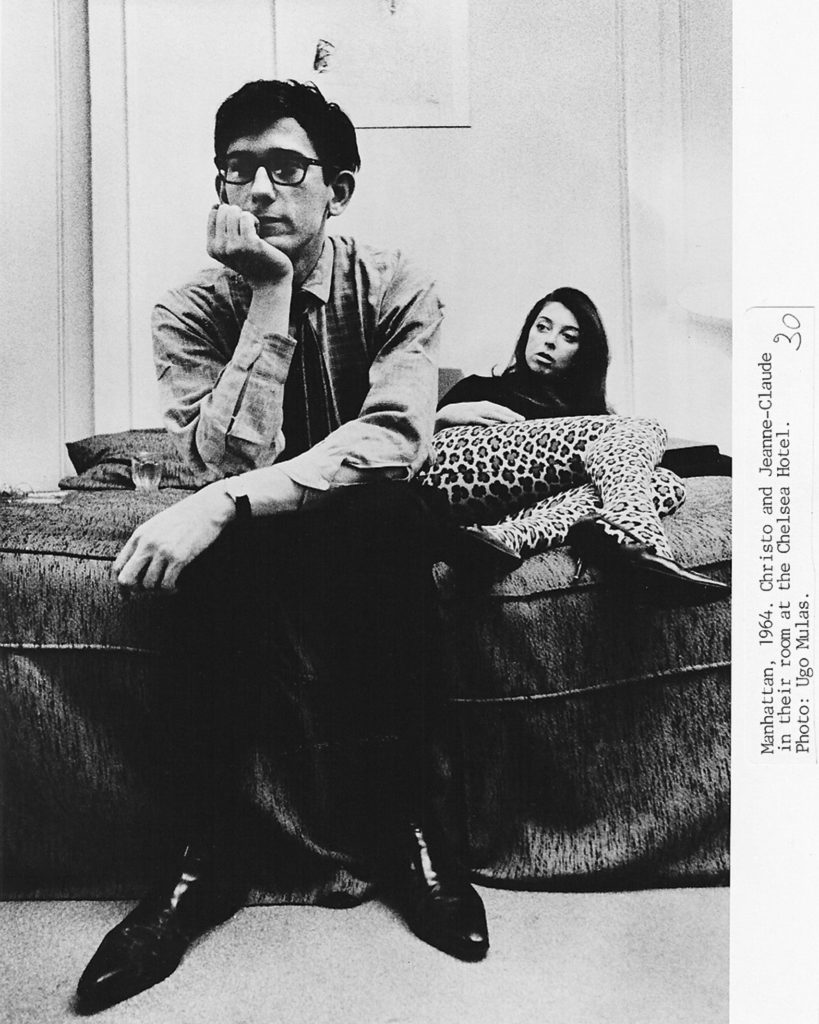

As fate would have it, both were born on June 13, 1935, he in Gabrovo (Bulgaria) and she in Casablanca, and, after meeting in Paris, they never left each other’s side: “Until death do you part.” And it was unfortunately death that once again intertwined Christo’s own destiny with that of another great name in contemporary art: Germano Celant, who passed away a month before Christo, and with whom Xto had revisited the long series of installations by Xto+JC in another book (The Water Projects)2 Germano Celant, Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Water Projects, Silvana Editoriale, Milan 2016 , which covers all their greatest projects on an urban and territorial scale, from 1961 to 2016.

READ ALSO – Why is the awarding of the 2020 Pritzker Prize to two FEMALE architects – still make the headlines?

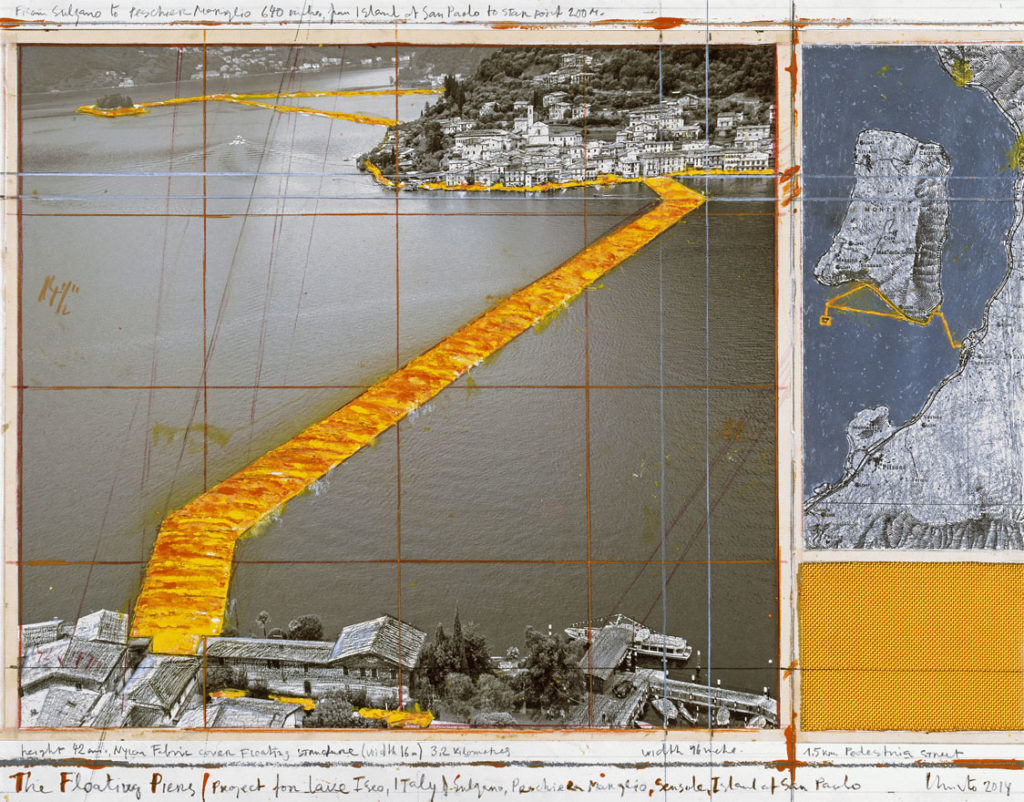

Nearly 60 years of work, culminating in the “miraculous” Floating Piers installation on Lake Iseo. Once again, half a century after having wrapped two Milanese monuments (1970) and the Aurelian Walls in Rome (1974), Christo had returned to Italy, led by the apostle Germano.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

So what’s next? With a distressing number of people, artists, and friends having passed away (the list is grievous) this seemingly endless spring/summer 2020 season might be the perfect time to stop and reflect on the meaning of life and death. What’s the use of a life spent in pursuit of dream-like projects, trying to perform miracles?

What’s the value – if not the meaning, superfluous – of the great works meant to challenge Nature (in a good-natured, ironic, and sometimes almost comical way), which Christo always exalted, however, in the end, with his immense machines to be admired and explored, his im-possible impositions on citizens (city dwellers), and his deformed natural/artificial landscapes? There will be time to reflect on this.

Meanwhile, The Show Must Go On, meaning the same show prophesied by Guy Debord in his Society of the Spectacle. And that which will remain of it will be the images, the books, sometimes the voices, and the feeling of déjà vu/déjà vécu that are inevitably reminiscent of Christo’s projects, where seen in real life or in effigy.Celant was the last great conductor: the minister (or commander, as Giancarlo Politi saw him at the first meetings of the authors of Arte Povera) of ceremonies invented for a secular religion, that of art, which certainly explains at least one thing to us.

Just like the works of Nature, objects, buildings, and all other works of mankind, whether masked or not, have and contain a soul. And that soul is not necessarily always that of their makers.