Running from 10 September through 15 November, Thom Mayne’s solo exhibition “Sculptural Drawings” will be held at the Tchoban Foundation, the museum of architectural drawing in Berlin: the show collects the drawings and artworks (plastic models) made by the Californian architect from the almost 50 years of his professional career. To celebrate his work Stefano Casciani has written this introduction, which will be included in the catalogue published by the Tchoban Foundation on this special occasion.

I’m looking for something that produces a likeness to the idiosyncrasy of the individual, the unpredictable element of human behavior.

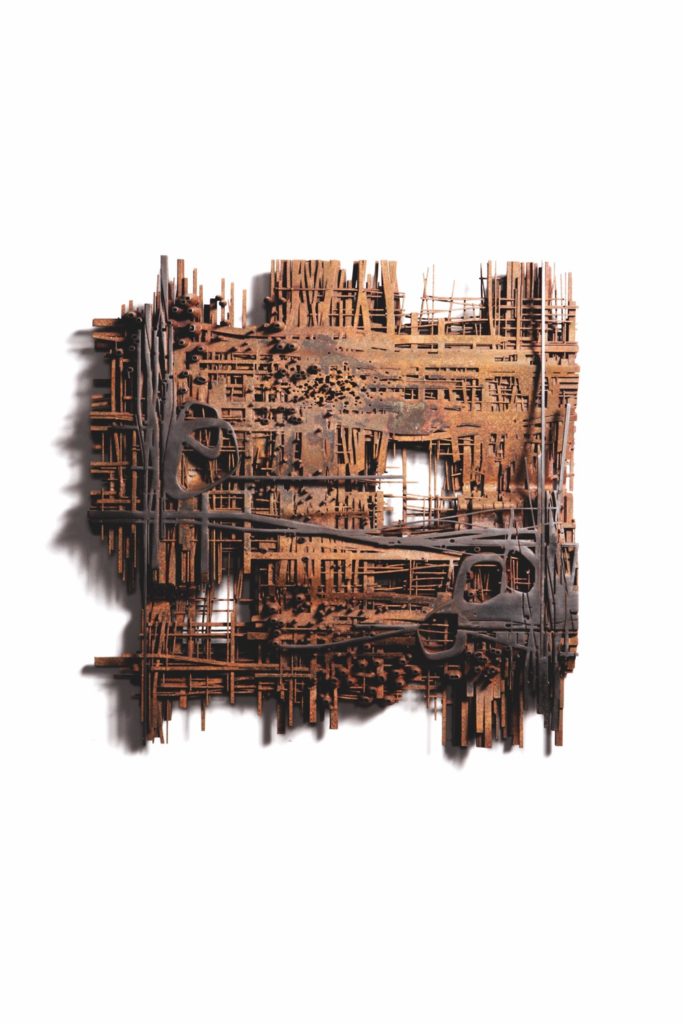

Thom Mayne, Strange Networks, 2020

“Planning” has been since always the act of foreseeing new realities, divining an unexpected but possible future, the shape of things to come that only our brain and soul could see in a not too distant future. Techniques and technologies would have helped in this, making our act of planning easier and possibly more successful, eventually. But all this would have been meaningful under one only condition, that our limited capabilities of calculation as humans would have been supported by our capacity of divination, i.e. the effective imagination of better and improved “things”: object, products, artifacts, buildings, cities, territories.

1988/92

And what if some new, incredibly new technologies would completely redefine not only our act of planning, but even our act of “seeing” the future, and the engine behind it, i.e. our brain? Until possibly a decade ago, none (especially no designer) would have thought that something like this could happen, that the Artificial Intelligence would have been running so fast and with its unprecedented speed would have been changing even our perception of this world, and of other possible worlds to come.

Thom Mayne has worked for some time on this increasingly blurry boundary between the as-yet unexplored potential of the human mind and the possibilities of development of new worlds, first of all thanks to the mind’s ability to imagine, and then to the techniques of representation, from the pencil gripped in the hand all the way to Artificial Intelligence, by now an integral part the project and of the architecture for which the project is made. Over time, a highly dynamic evolutionary sequence emerges in his work, from the drawings on paper of the Lawrence Residence (1980) to the reliefs of the Crawford Residence (1988), the montages of the Nara Convention Center (1991), all the way to the turning point of the Giant Interactive Group headquarters in Pudong (China, 2010), which marks the beginning of a long, important series of two/three-dimensional models that go by the name of Combinatory Forms.

Along this entire path, however, Thom has never approached the project with a preset attitude, and certainly not with an ideological stance. Like any designer, architect, writer, director or artist worthy of such titles, Thom does not know – and perhaps does not even want to know – exactly what will emerge from the creative process: he does not have a predetermined form in mind, nor does he think about a style, a “sign” or a “signature” to which the project, the building, the city he imagines will have to correspond. Instead, he is very interested – almost obsessed, we might say – in and by an idea: that by studying the possible life inside the building and, as a result, its volumes and shapes, the full and empty zones that develop around it, granting the project that certain degree of indeterminacy that belongs to the life of people, spaces and structures can arise which those who inhabit them can recognize as a new aesthetic experience.

To live in architecture and to make it live, like its every inhabitant or designer, is this type of experience, original and different from the experience one has of a work of art, because it is not pure ecstatic enjoyment of beauty: instead, it involves the dimension of time and movement, like the action in a film, where the actor and viewer always cross the space in different ways, with a mindset that changes depending on what they encounter and perceive, hence each creating his or her own personal film: or work of architecture, in our case.

The possible combinations with which to configure the initial form of architecture, which its inhabitants will live and recreate anew each day, are undoubtedly infinite, as are the different individual visions. And it is precisely this freedom of configuration that for some time now Thom has also demanded of the machine, of the Artificial Intelligence which is not (or no longer) an adversary but an ally, to be “trusted” in its continuous suggestion of possible alternatives, be they dozens, hundreds, or perhaps thousands.

Because it is precisely in the choice of one (or more) of the infinite possible options proposed by the machine that we can identify the craft, the art of the architect today. Just as a writer uses only some of the thousands of words that exist in the dictionary (and seldom, in increasingly rare cases, invents new ones), and his art lies precisely in that choice of words and their sequence; just as the director chooses only the shots he considers best from all the possible angles on the action he wants to portray, and in the editing refines the work he has already begun; so the architect Thom imagines himself (successfully) to be gets down to work, every day, aided by Artificial Intelligence, in the interplay between choice and chance, reason and emotion, perception and prediction.

This potential indeterminacy of the design object, in its ability to be many things, also very different from those the designer has envisioned, in the end also has something to do with the desire, the passion of Thom to teach other, younger people how to become architects, or simply dreamers of architecture. As anyone knows who loves the job of teaching and therefore does it well, the greatest satisfaction in educating new designers (or writers, musicians, painters) comes in seeing their hands and minds produce something we would not have imagined ourselves, but to which our teaching made a contribution, along mysterious paths.

READ ALSO – Thom Mayne: the bad boy of architecture

So do not look at the beauty of these attempts to interpret the world – in form and matter, of paper, wood, steel, resin – only as works of art, extreme and often arduous syntheses of desires that are very hard, at times impossible, to fulfill. Each of them contains the seed of knowledge, of that ability to interpret the world that has cost Thom Mayne, and all of us who love architecture, an infinite time of “sharpening, like a good pencil,” as Ernest Hemingway suggested in the case of writing: and that in the limited time of the school, in the never sufficient hours spent together with the young, we can only sow, without really knowing what plants will grow. In the best – or simply the luckiest – of cases, the work will give rise to new personalities, to other new and marvelous ideas of objects, architecture, cities.

Observing them with great attention, in a small detail, perhaps a random interweaving of lines or surfaces, we seem to recognize ourselves, to see the portrait of that Self for which we have always searched, with obstinacy, almost with desperation at times. And sometimes, by stubborn effort or simply through a lucky space-time coincidence, we are able to find it, to be certain we have really lived and not just imagined that world whose existence, now or in the future, we ourselves are prone to doubting on occasion.