The concept of the workshop was at the heart of the manifesto, Gropius writes: “the school is the servant of the workshop.”

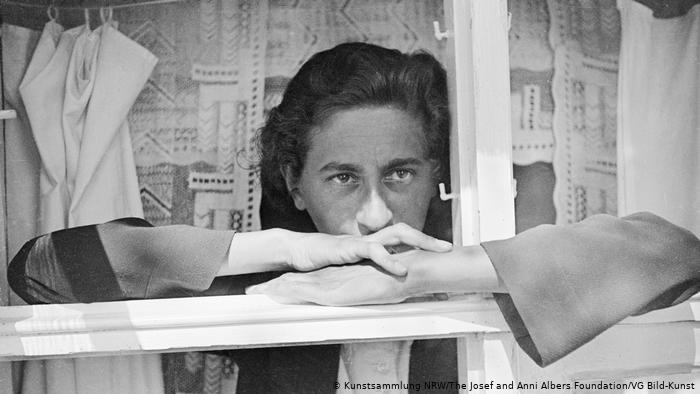

“The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism” is a wonderful journey experienced through Nicholas Fox Weber’s eyes. He was the head of the Albers Foundation and lived many years in company of Anni and Josef Albers.

Anni was much more than a textile artist; she was the inspiring professor and an artist (challenging glass, metal, wood, and photography).

The Albers uncovered and shared with him their own memories, stories and anecdotes on the exciting, glorious days at the Bauhaus school with their fellow artists and teachers, Walter Gropius (the silver prince), Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as well as with lesser-known female figures and artists (often in the shadow as wives and girlfriends).

Weber looks behind the scenes of the pioneering art school in Germany’s Weimar and Dessau in the 1920s and early 1930s, and captures the spirit and flair with which these Bauhaus geniuses lived, as well as their visionary trajectory of making art and architecture.

How did it all start? Walter Gropius was the founder and charismatic figure of The Bauhaus (originally named Bauhütte) the revolutionary German art, design and architecture school. Its roots go back to Weimer in 1919, then it was forced to move to Dessau and dismantled in Berlin in 1933 by the rising power of the National Socialist government. The mission of the school was to reunite traditional craftsmanship and artistic expression as one in the same daunting endeavor of teachers and students to work together elbow-to-elbow.

The main focus of the school was a new multidisciplinary approach to creating functional objects and “living spaces” that combined experimentation with formal design and modern (industrial) technology for the improvement of the general society. “In both pedagogy and practice, the Bauhaus emphasized form as an expression of function in design. Formal aesthetics were highlighted as a means of creating highly functional and visually appealing works, which could be used and enjoyed by all”, wrote Lisa Flanagan.

The school embraced the principles of modern technology to support the artist-craftsman in creating products both efficient and affordable for a large spectrum of people. Added to the curriculum in 1921, The Bauhaus Stage Workshop was conceived as a Voorkurs (preliminary course) where formal principles and properties could be tested by means of live enactment or performance.

If Walter Gropius’s 1919 manifesto had proposed a radical vision for a new institution that would erode distinctions between artists and artisans, it was the school’s unprecedented pedagogy, that propelled this revolutionary ideal into a new dimension. The famous Preliminary Course (Vorlehre or Vorkurs), investigated what Bauhaus masters considered to be the fundamentals of any artistic endeavor, whether applied or fine.

Supervised at first by Johannes Itten, then jointly by László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers, and finally by Albers on his own, the course explored theories of color and form, principles of composition, studies of materiality, exercises in life drawing, and visual analysis. More specialized courses in theory led by Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, and others supplemented the Preliminary Course. The various experiences and exercises students performed in these courses represented an effort to promote a holistic education.

The Course led students to enroll in specialized workshops devoted to specific crafts such as sculpture, ceramics, weaving, carpentry, printing, metal, or stage design. The concept of the workshop was key for Gropius: in his manifesto he wrote: “The school is the servant of the workshop.”

READ ALSO – Casa Batlló : the shrine designed by Antonio Gaudì in Barcelona

Inspired by the Renaissance “bottega” and the system of the Medieval guild, Gropius conceived, organised and directed the orchestra of the Bauhaus workshops where students worked as apprentices, dedicating years of practice to specific crafts, and learned by designing and executing products following the instruction of masters (both artisans and artists). The workshops represented a form of practical education in which students had the opportunity to apply the principles learned in the Preliminary Course to the hands-on process of design.

After completing one of these specialized workshops, only select students were to be admitted to the study of building. As “the ultimate goal of all creative activity,” building was the locus where objects produced in the various workshops (pottery, tapestries, stained glass, lamps, and the like) were to be brought together. Building figured prominently at the center of the Bauhaus Dessau location. This ambition however was not fully realized until the final years of the Bauhaus; the school offered no formal courses in architecture until 1927, before which students could only gain experience by apprenticing in the private architectural practice of Gropius and Adolf Meyer.

The divergent trajectories students might follow at the Bauhaus were represented together in the curricular diagram. The singularity of the circle suggests the holistic nature of a Bauhaus education, in which individual students representing diverse disciplinary backgrounds were to come together in pursuit of a shared mission to reform art, design, and society. Female students were generally encouraged to attend the textile laboratory based upon handcraft skills and two-dimensional conceptual thinking. Anni Albers is considered the foremost textile designer of our century. Albers, one of the central figures of the Weaving Workshop at the Bauhaus, had an enormous effect worldwide on the design of yard materials and on the creation of singular weavings and wall hangings.

“Young people of all lands come to the Bauhaus”*.

Students were both male and female in an ever shifting proportion. The ultimate goal of all art is the building! Architects, painters and sculptors had to relearn to perceive and understand the composite character of a building both as a totality and in terms of its parts.

“The Bauhaus wants to serve the development of modern housing – from the simplest household appliance to the finished dwelling. Convinced that household appliances and furnishings must be rationally related to each other, the Bauhaus, through systematic research work in theory and practice and under formal, technical and economic aspects, seeks to derive the design of an object from its natural functions and conditions. An object is defined by its nature. In order, then, to design it to function properly – a vessel, a chair, a house – one must first of all study its nature; for it is expected to serve its purpose perfectly: it must fulfill its function in a practical way, be durable, inexpensive and ‘beautiful.’ It is only through constant contact with advancing technology, with the discovery of new materials and new ways of putting things together that the creative individual can learn to establish a living relationship between the present time and tradition and thus develop a new approach to design.”*

Limitation to typical primary forms and colours that everyone can understand. Simplicity in multiplicity, economical utilization of space, material, time and money. The creation of prototypes of objects for everyday practical use is a social necessity. The needs of the majority of people are, on principle, similar. The home and its furnishings are matters of mass demand, and their design is more a matter of reason than a matter of passion. The Bauhaus workshops are essentially laboratories in which prototypes of products suitable for mass production and typical of our time are carefully developed and continually improved. In these laboratories, the Bauhaus wants to train and educate a new type of worker for industry and the crafts who has an equal command of both technology and form.” (quoted in Bauhaus-Archiv 7)

When the new provincial government threatened to cut off the school’s subsidies – as the Nazi factions in the region supposed that all those foreign-looking students were Jews or Jewish sympathizers – Gropius moved the school to Dessau in 1925 (southwest of Berlin, it was an engineering and manufacturing center). There, for the first time, the Bauhaus built itself a campus. Gropius, now one of the most famous architects in the country, oversaw the design of the main buildings and the masters’ houses. The workshops, which he also designed, provided everything: textiles, fittings, door handles, murals, and tableware. The furniture was produced in the joinery of Marcel Breuer, one of the first and youngest students at the Bauhaus.

READ ALSO – Penthouse One-11: the sinuous Zaha Hadid watchtower at Citylife

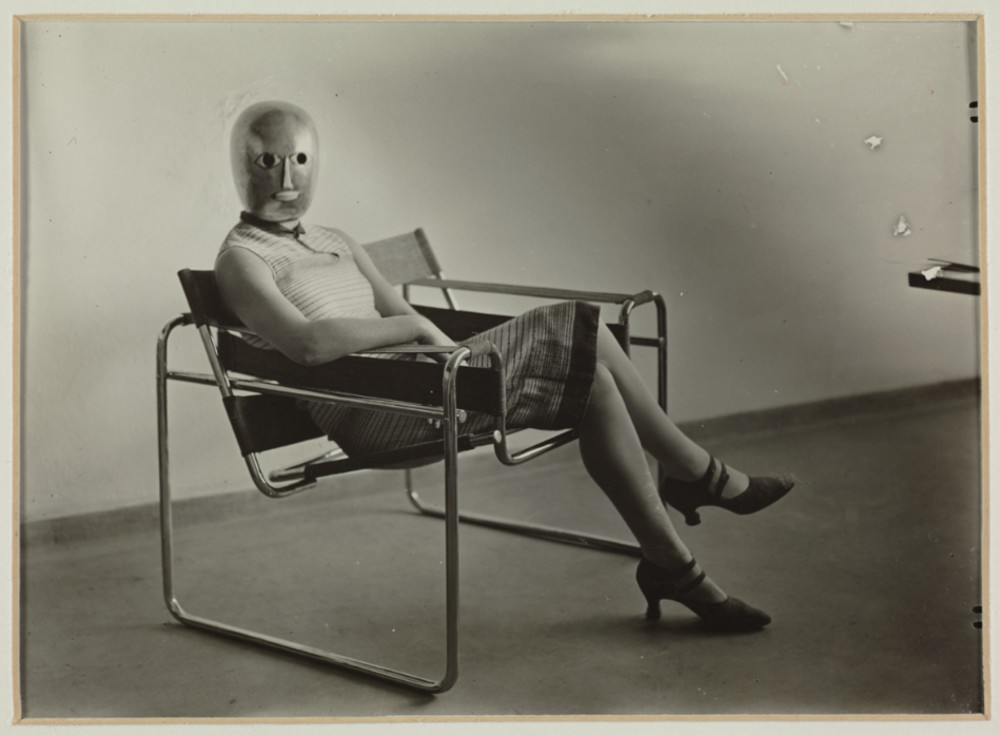

The evolution of a single design gives a sense of how the Bauhaus grew. For his Model B3 chair—also called the Wassily chair, in honor of Kandinsky, who expressed admiration for its prototype—Breuer took inspiration from the elegant handlebars of a milkman’s bicycle, made of seamless tubular steel, a new material. He created an industrial-age club chair that, reduced to its metal frame, seemed to levitate in space. Like all the furniture Breuer designed for the school, it was also a collaboration: the school’s textile workshop contributed the seats, woven from a strong cotton thread. And, as with many great Bauhaus designs, it is an example of materialized reasoning. It solves the formal problem of creating a substantial piece of furniture that is both there and not there. It is interesting from every angle, and especially beautiful from the back.

When the Bauhaus school reached the end of the tether, students of jewish origin fled to safer countries, its name became a synonym of the “international style” and Gropius was part of its global dispersal (from London, Rome to the USA). His book “The new Architecture and the Bauhaus” is a milestone and the famous 1938 MOMA exhibition of the Bauhaus artefacts in New York led the path to immortality.

Source:

iBauhaus: The iPhone as the Embodiment of the Bauhaus Ideals and Design, Nicholas Fox Weber (feb 2020 Knopf)