Patricia Urquiola balances the sustainable quality of wood with formal creativity in a project for Listone Giordano.

Confronting the world’s unexpected changes is an increasingly arduous task, ever since the shattering of the positivist dream of “magnificent and progressive destinies”, which would necessarily be fostered by a constant spread of increasingly liberating technologies.

For however reasonable it is to surmise that technological progress also entails improved living conditions on the planet, it’s quite another matter to engender the actual materialisation of this improvement. Between saying and doing, there’s the ocean of consumerist ideology, disguised as an incentive to focus on the quality of private space, regardless of the conditions of public space.

Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola

Thus the individual desire for a sumptuous living, both in its functions and aesthetics, has to reckon with a constant stimulus to buy and use new products.

Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola

Such products aren’t necessarily better than their predecessors, and sometimes they disadvantage a better overall balance in the management of natural resources.

This condition becomes a paradox in the world of interiors. In this well-seasoned market subject to the laws of the goods system, the same companies that are expected to generate ever-increasing turnovers must also guarantee durable products that their customers will decide to live with every day for many years.

This paradox surely has more chance of being overcome, if not resolved, in the furniture market. Here, at least 70 years of Italian design history have spawned and consolidated a “culture of alternation” in which shapes and materials follow on from one another, with repeating cycles normally accepted by higher- end consumers.

READ ALSO – Kālida Sant Pau: when architecture improves the quality of life for people with cancer

Willing to spend their money on an iconic product, whether it’s old or new, these consumers are subject and in some sense accustomed to the seasonal gimmick, to the whim of the moment and even the stagnant repetition of old styles and materials passed off as novelties (the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, velvet, wenge-coloured walnut, shagreen, and so on).

Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola

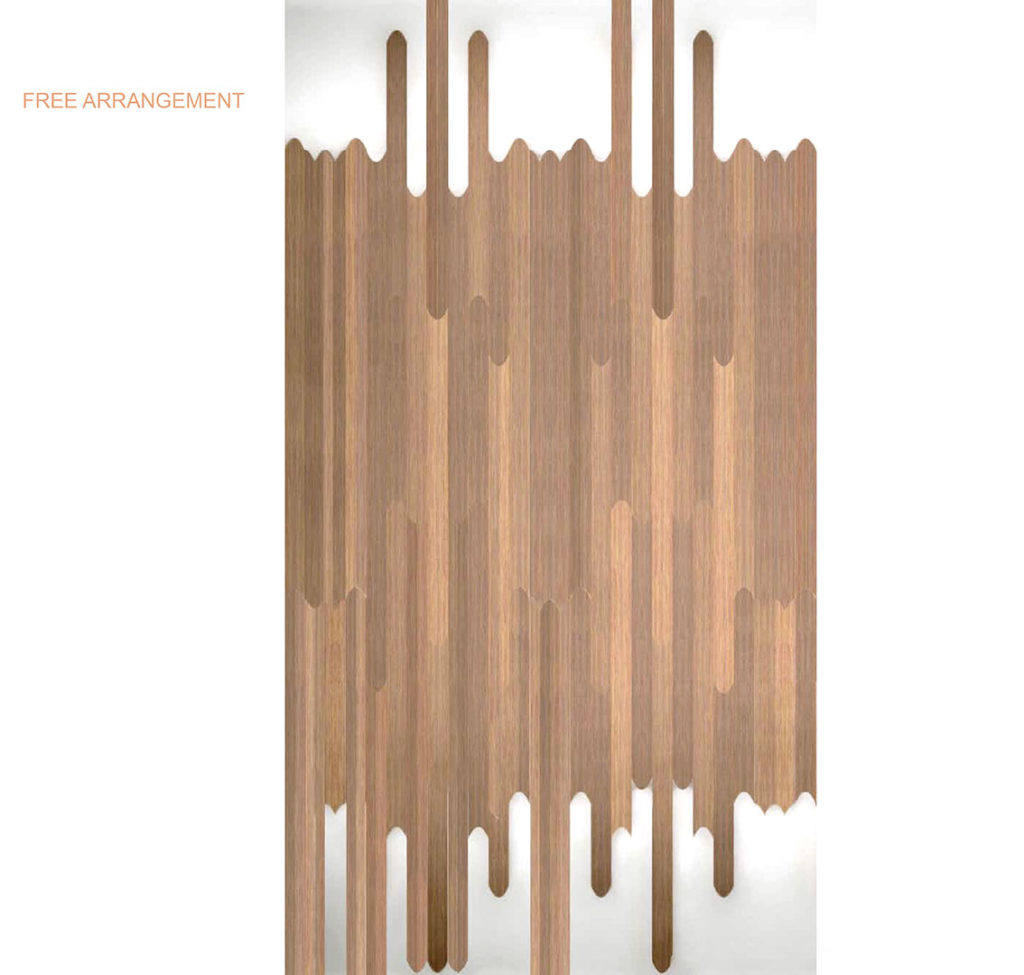

Biscuit is a project that is developed around the concept of softness and

Patricia Urquiola

is characterized by a free composition of lines and shapes.

It’s fine if some industries – perhaps originating with specific materials that made their fortunes – continue to diversify both these materials and their production techniques in order to hold the attention of their buyers, confiding in designers who are sufficiently eclectic and uninhibited to tackle the commission.

But what can a company do if it doesn’t want to abandon the use of wood, and even insists on raising its customers’ awareness regarding the most important quality for the future of environmental equilibrium?

Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola Moodboard project | design: Patricia Urquiola

This is the sustainability that all manufacturers talk about but few are ready to face, and even fewer are organised into an integrated programme encompassing the entire cycle of materials, production and consumption.

Certainly, you can’t just paint yourself green and call yourself “sustainable”. One can only define oneself as such after a tried-and-tested journey such as the one travelled by Listone Giordano. This firm introduces its products to the market at the end of a long cycle of green procurement that respects “natural” methods and timeframes, starting from the cultivation of trees with a centuries-old procedure rooted in French culture.

This method has been carefully and intelligently adapted to the Italian context through non-polluting processes, to obtain an end material distinguished by the company’s Biosphera* branding system, as well as the FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council®) and PEFCTM (Program for Endorsement of Forest Certification Scheme) certificates, which guarantee the sourcing of wood from forests managed in compliance with precise environmental, social and economic standards.

And yet this ethical approach does not seem to be enough on its own. Anchoring oneself to rigorous environmentalism, which concedes little or nothing to aesthetics, does not come without its risks. Indeed, it can be misleading in such a unique market as that of the home, which is very sensitive to fluctuating tastes and susceptible to constant variations.

READ ALSO – Igniv Restaurant: the taste nest in Switzerland

Listone Giordano – who has based the recognised quality of his production on genuine sustainability – also had to consider the special qualities that his undoubtedly ecological production could acquire by meeting with designers of different methods and approaches.

Studio Urquiola – Milano Studio Urquiola – Milano

One of these designers is Patricia Urquiola, who started her dialogue with Margaritelli in 2012. Her work typically combines reflection and intuition, vision and experience, lightness and depth. Before arriving at a design proposal, she let some time pass as a useful way to establish a balanced dialogue with the producer, the technicians and the available technologies. The initial request to work on a surface treatment, as the designer had done in the past with other materials, was reconsidered to make space for a domestic- oriented analysis of horizontal finishings for the home (and by extension for other convivial contexts such as hotels, restaurants and various types of public places).

A floor is not just a surface to walk on more or less distractedly, but rather a very delicate area of equilibrium in the genesis and daily life of a space. One could list its many symbolic values – a partition between sky and earth, a zone of respect for nature that isn’t always eco-friendly, a shelter from the rigours and hardships of everyday life, and on which we can do far more than merely walk. In short, it is tongue, howling design errors, or the witticism as an end in itself are always lurking in ambush. How many houses – which are otherwise perfectly up-to-date and with many well-defined details – slip up on trivial mistakes such as the wrong material, composition or color of the flooring?

Biscuit 05 small – print test | design: Patricia Urquiola Biscuit 05 small – print test | design: Patricia Urquiola Biscuit 05 small – print test | design: Patricia Urquiola

In the dialogue between Margaritelli and Urquiola, the design of a continuous surface became oriented around a system of components (Biscuit). This approach drove the flooring to become an object in its own right, in terms of the naturalness of the material used to make it. It’s not just a question of shape with the staves’ distinctive rounded ends, but also of the essence of the production method and finishing.

READ ALSO – Patricia Urquiola. Design, precision, creativity

It wasn’t the designer who adapted to the technique and machines, but rather the other way round. Instead of mass-production machining, where the material emerges from the manufacturing chain standardised by a single robotised procedure, the product’s manipulation is closer to that of a one-off piece or small-run edition.

Numerical-control processes are applied all around the edges of the wooden boards, and each component is reworked several times – as can happen for the legs of a chair or tabletop. Considering that 1 square metre of flooring comprises up to 100 elements, the average surface of a house (100 square metres) can include up to 10,000 elements. This highlighted the suitability of employing a diversified mass-production process, where the quantities justify the great attention to detail, while also motivating the development of sophisticated equipment for robotised manufacturing.

Margaritelli recognises the designer’s power of conviction, which the company needs in order to make an important step forward in the technological field. This advancement wouldn’t have occurred otherwise, or may have required far more time to emerge. After all, Patricia Urquiola is well-known precisely for having injected the Italian design logic of transformism with a “bright spirit”, which is closely linked to her highly outgoing character and her desire to (literally) weave ever-new design stories, as if every material can be likened to a fabric, and as if every product resembles a garment.

Studio Urquiola – Milano Studio Urquiola – Milano Studio Urquiola – Milano Studio Urquiola – Milano

If the house is the person, and if its spaces also represent the individual’s complex psychology, then Urquiola’s products are furnishings to wear, clothes to inhabit that are almost made to measure. This weaving operation in her work has also proved successful in the design of a wooden

flooring, as well as in the encounter with the environmental coherence and conscience of Margaritelli family, thus scoring a point for expression in design’s tough match against market laws and expectations. And in the advice of Achille Castiglioni – whom Urquiola acknowledges as a mentor for his persistence in always inventing new things – these laws and expectations weren’t even worthy of consideration.