Artifice and nature: an antinomy, a paradox that has always concerned art and science but that for at least two centuries has plagued business-people and designers, conservatives and evolutionists, builders and environmentalists. In the contemporary dialectic between the industrialized production of artefacts and protection of the natural environment, the search for shared rules is vital – as with any social pact – to at least try to address (if not resolve) this paradox, reconciling the needs of the market economy with the protection of the planetary environment.

So if in a transgressive and violent society like the contemporary one these rules don’t exist, or function, are not applied, or are simply ignored, what do you do? It becomes necessary to invent new ones, dedicate a substantial part of industrial design to controlling the ecological quality of the processes and products: perhaps rediscovering their origins, and prior to that the genius loci of the land where the business was born.

Warehouse sketch from ABDR Architects for the selection of Italian Pavillon

at the Biennale di Venezia 2010

Thus Margaritelli, born at the end of the nineteenth century at the dawn of the great era of Italian industry as an enterprise for forestry work and the transformation of wood, poised between the agricultural world and the industrial one, has developed its business strategy accordingly: between the creation of mass-produced, high-quality wood products and the search for solutions for the cultivation of trees that does not alter the equilibrium of the forests.

READ ALSO – Wood culture

The finest inspiration for this latter possibility comes from centuries-old French culture that has always considered the integrity of the forests and the life of individual trees as a common good to be maintained rather than mere commodities to exploit: a conviction that has deep roots in a long history of forestry protection, of which the earliest reports date back as far as the Middle Ages when feudal lords and monastic orders took action to protect this irreplaceable resource used for many applications, starting with construction.

The forest of Cîteaux in Burgundy for example, was planted in around 1000 AD by the Cistercians, who have looked after it since then and passed it down to successive generations. It was also in Burgundy that Margaritelli honed their strategy for forestry, analysing and making their own the methods and rules that have enabled the forests of France to achieve and maintain an impressive extension: 17 million hectares of productive forests in which every tree is surveyed, cultivated, cut and then systematically reforested in compliance with the old laws.

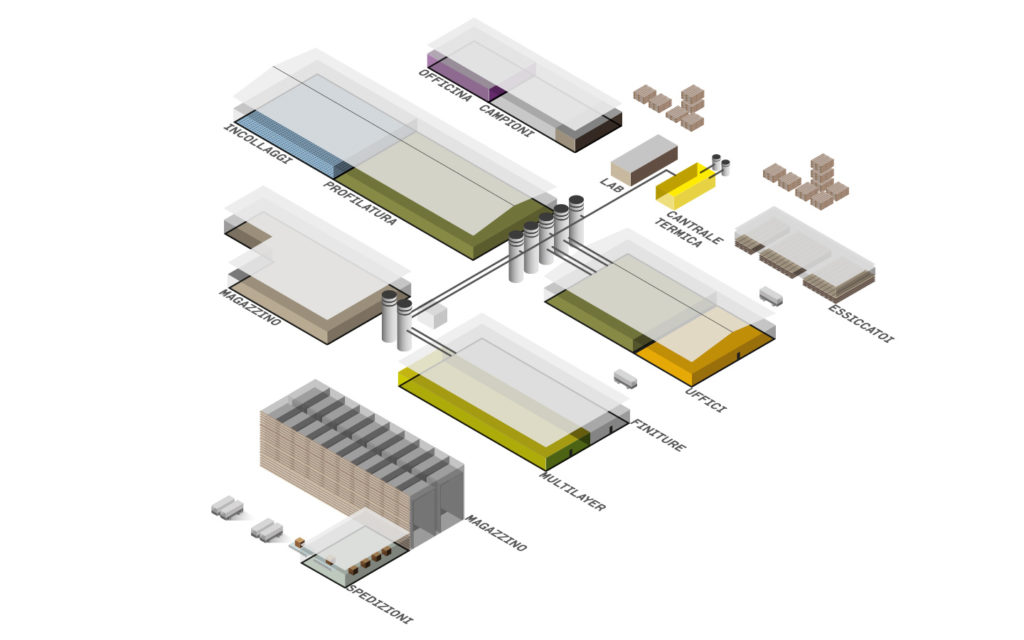

The same practices that Margaritelli follows in its sawmill in Fontaines established in 1961, and in the Umbrian forests, where the factory for the most sophisticated Listone Giordano production is based at Miralduolo in Torgiano.

As fate would have it, originally in this area the Fernando Margaritelli after World War II cultivated his vineyard, an area therefore with an agricultural vocation that over time was transformed into a place designed for high technology and sustainability over the medium to long term. If in fact the procurement of wood material respects the rules of environmental equilibrium, if the treatment processes in the factory do not generate polluting agents or at least are controlled and reduced in toxicity, one can think of Listone Giordano as a new kind of factory, made precisely from the nature of the forest and the artifice of the industrial workshop.

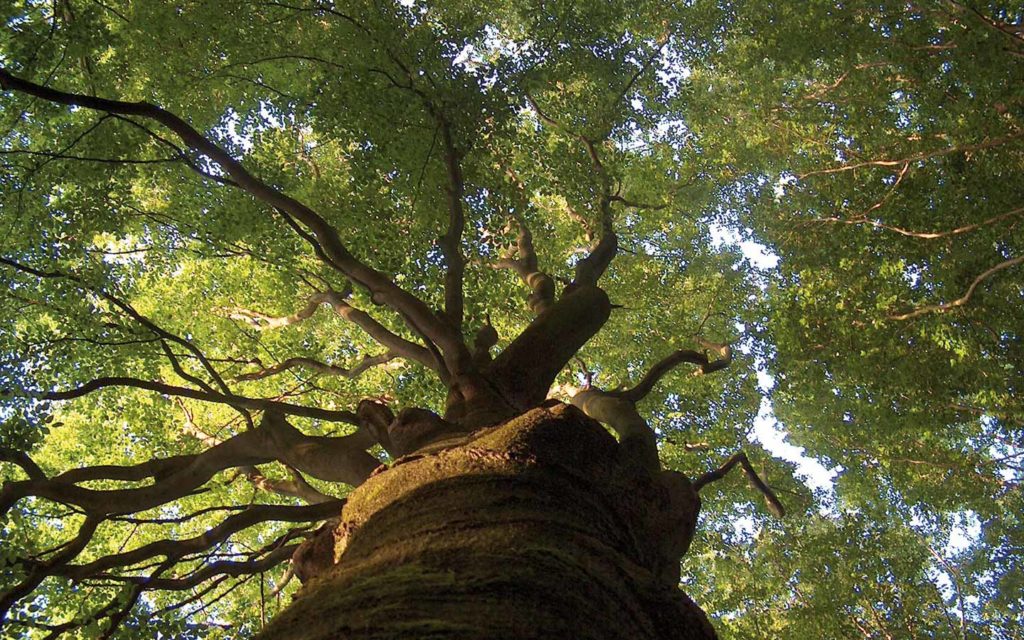

It is the Tree Factory, the utopia of a production cycle that comes close to the natural one where matter is constantly auto-regenerated and multiplied, in which every tiny part contributes to the survival of the whole, for which the very concepts of refuse or waste simply do not make sense, because they do not exist.

This positive idea of industry as a possible producer of a new culture of sustainability, is connected to the notion of design as a philosophical reflection on the nature of living space. In a lovely conversation between disegno, Andrea Margaritelli and Michele De Lucchi – one of the designers for Listone Giordano – the latter with such a capacity for synthesis that he has actually reflected on the idea of “home” as an internal landscape in which dominate the ceiling and floor: two horizontal elements that are so to speak uranic, in other words linked to the greater natural space of which Heaven and Earth are the visible confines.

READ ALSO – Natural Genius: a ten year long journey investigates the industrial design applied to wood surfaces

In this view, even a floor (often neglected, even though it carries out such an important role in the definition of the interior), even of industrial production, requires a non-consumerist approach, conditioned less by the concept of luxury and more by the idea of duration: that is typical of creatures like trees, with their constant regeneration in the seasons and bad weather, living up to hundreds of years if external factors (like senseless deforestation) do not interrupt their life cycle.

Even a floor, a parquet, can last a very long time. Above all if when one takes a decision about it, rather than buying it one acquires it, by making it part of everyday existence experienced through things: a kind of investment in the idea of a slower tempo, or at least slowed down with respect to the frantic pace of mindless consumerism, in which the ageing of objects is not a defect but a quality.

The patina of time gives value to things instead of removing it, it makes them more similar to the inhabitants of the houses, that despite all their uncertainties and complications are still the closest things to natural beings it is given to know.

In this strategic vision of the Margaritelli Group – where the sense of time, growth and maturation has a primary role in the definition of the product – what returns (for coherence, necessity, noblesse oblige and respect for geographical and cultural roots) is a passion not just for technical discovery but also artistic.

The sky is blue forever, and the earth will endure, and bloom in spring again. But you, Man: how long will you live?

Gustav Mahler, Das Lied von der Erde/Il Canto della Terra

Whether it is the industrial application of a invention patent (the one developed by the researcher and lecturer Guglielmo Giordano, who devised the method from which the leading company in the group takes its name), the support of major exhibitions of old masters (Michelangelo, Raffaello) or the acquisition of a rare work (the fifteenth century Bambin Gesu delle Mani by Pinturicchio), the strategy is the same: act local/ think global, to preside over a world market, increasingly wide and increasingly difficult.

All this without betraying their origins and identity, founded in a complex and tormented nation such is Italy but that for many centuries has succeeded in the very difficult reconciliation of the artificial and the natural.